SHARPE’S BMI

When General Joseph Hooker took over the Army of the Potomac from Ambrose Burnside on January 26, 1863, he had a lot of corrections to make in its operations. One of his biggest problems was the field intelligence network, or lack thereof. George McClellan had Allan Pinkerton and his Secret Service. This of which favored the General’s outlandish view on enemy strength and numbers and subsequently left with McClellan upon his permanent removal in fall 1862 leaving General Ambrose Burnside with practically nothing besides the civilian contractor John Babcock. Babcock did his best during the early winter of 1862-1863 but Burnside payed little attention to what info he was brought. Hooker inherited less than what Burnside had from McClellan but did retain Babcock. He alone, though, was not up to the task of reorganizing the tainted name of the Secret Service. Even General Marsena Patrick, the Provost Marshal, was swamped with the added work. Both Hooker and Patrick needed someone to carry out the intelligence gathering wing and early prisoner processing. After careful consideration Hooker looked to the 35 year old commander of the 120th New York Volunteer Infantry, a successful lawyer from Kingston, New York named George Henry Sharpe. Sharpe was a graduate of Rutger’s University (at age 19), had studied law at Yale, and was mentored at one of the most prestigious firms in New York City. In 1861 he answered the 90 day volunteer call and was the Captain of Company B, 20th NY State Militia. When the unit’s enlistments ended and was aimed to be mustered in as a 3 year unit, Sharpe resigned and returned to his practice until Lincoln’s call for 300,000 more volunteers in 1862. He was personally asked to raise a regiment and requested the numerical identity of the 120th in honor of his original unit. The 120th saw very little action with the most coming at Fredericksburg in December of that year, though that too was light in comparison. Sharpe was humble, was very well liked by his men, and was a great organizer and motivator. His acceptance as the head Hooker’s new intelligence organization didn’t come easily but he did feel as though he was needed. He constantly checked in on the 120th and remained its formal commander though he never led it again in the field.

Col. George H Sharpe

Maj. Gen Joseph Hooker

Provost Marshal Marsena Patrick

As there was no official department for military intelligence in the US military at the time, Hooker assigned the forming bureau to General Patrick and the Provost and in doing so appointed Sharpe an official Deputy Provost Marshal. Over the next few weeks Sharpe assembled a top notch staff and developed the name of his organization. A name that evolved from the Secret Service to the Bureau of Secesh Information before landing on the final verbiage of the Bureau of Military Information. Sharpe’s staff was small but highly effective. It consisted of John Babcock (his topographer and civilian head), Captain John McEntee (formally the QM Sgt of the 20th NYSM and a Captain in the 80th New York Infantry), Lieutenant Frederick Manning (of the 148th New York), and Captain Milton Cline (of the 3rd Indiana Cavalry) as his Chief of Scouts. Civilian contractor Judson Knight (a personal scout for General Phil Kearney and the successor to Cline in 1864 as Chief of Scouts), Daniel Cole (from the 3rd Indiana Cavalry), the Carney brothers (Edward and Anson from the 20th NYSM and 5th US Cavalry), and Martin Hogan (from the 1st Indiana Cavalry) were amongst the first and most prized prized scouts in Sharpe’s new roster. Throughout the war, over 240 names appeared on the BMI’s payroll as soldiers or civilian assets but few were in the field at a given time with 70 being the max number. Civilian Unionist in Virginia came under the BMI’s umbrella as well and were vital for scout and spy movements and gaining information themselves to pass on. Names like Elizabeth Van Lew of Richmond, Issac Silver of Fredericksburg, and Rebecca Wright of Winchester were invaluable assets as well as the local slaves and run away who readily shared information about their masters.

John C Babcock

Capt. Milton Cline Chief of Scouts

Capt. John McEntee

Daniel Cole

During their first field test during the Chancellorsville Campaign, the BMI showed itself to be an effective intelligence force in the field. During the Gettysburg Campaign it improved to show not only to Hooker but to the new commander George Meade, though very weary at first, that it was highly effective and highly vital. Before the two armies met in Gettysburg for the titular battle, Sharpe and his scouts knew exactly who all was with Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and where each piece was thanks to a network of signal stations, scouts in the field, and multiple agents within Lee’s own officer corps. By the night of July 2nd, The BMI had interviewed prisoners from every Confederate brigade and division except George Picketts of Longstreet’s Corps. That information was what convinced Meade to stay and fight on the 3rd and as to where Lee’s attack would drive towards. When General Ulysses Grant arrived east and led the push on Richmond, it was the BMI and its extraordinary abilities that brought forth a lasting bond and trust between Grant and Sharpe. This partnership not only brought Sharpe a Brigadier General’s promotion and a Brevet to Major General but the hidden key to Union victory. Sharpe would have scouts and spies in the war offices in Richmond, with Lee’s army, and everywhere in between and perfect the operation of the Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield. America’s first all-source military intelligence organization was a huge success and one that wouldn’t be replicated again until World War One.

Elizabeth Van Lew of Richmond, Virginia

Rebecca Wright of Winchester, Virginia

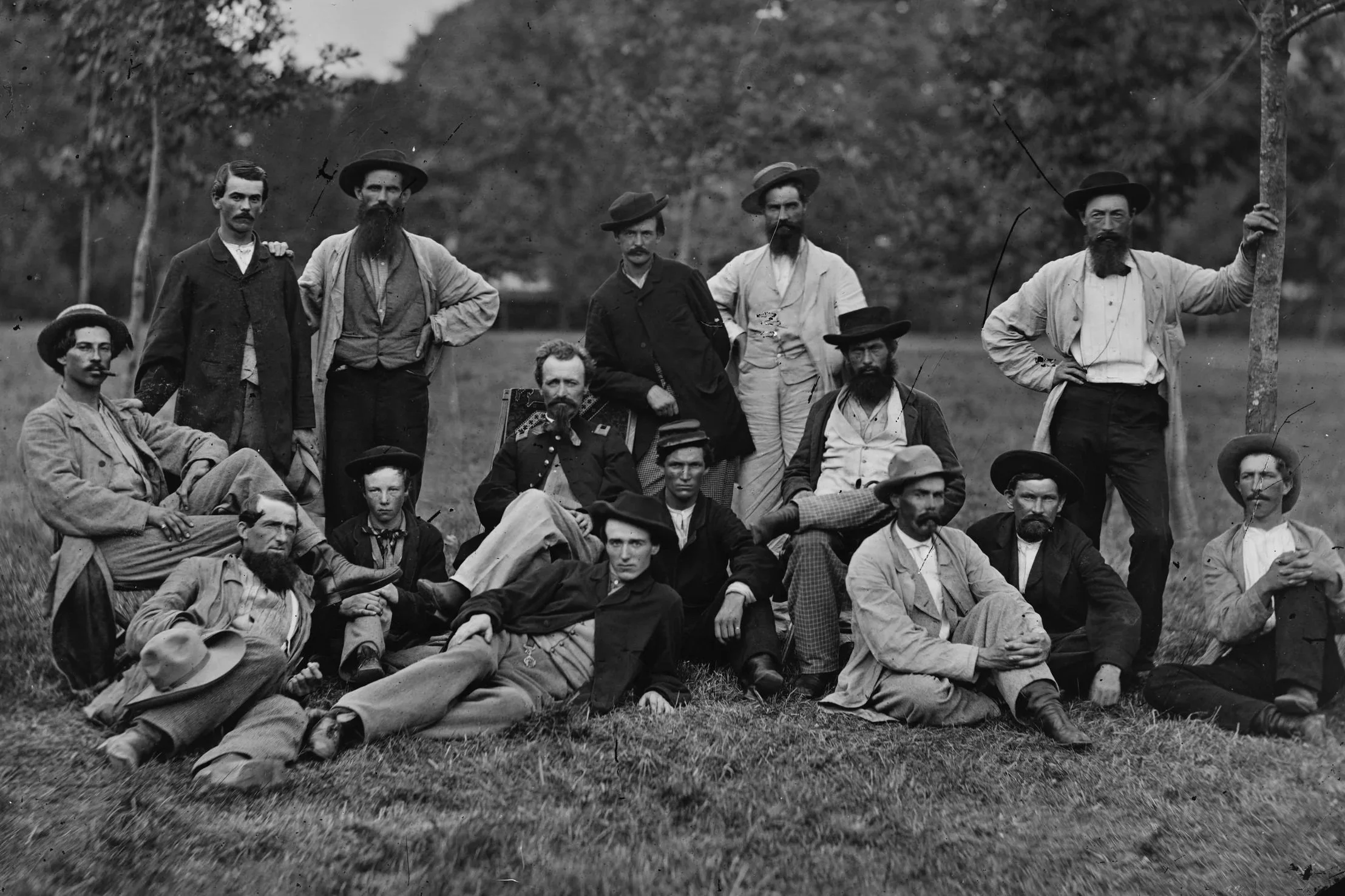

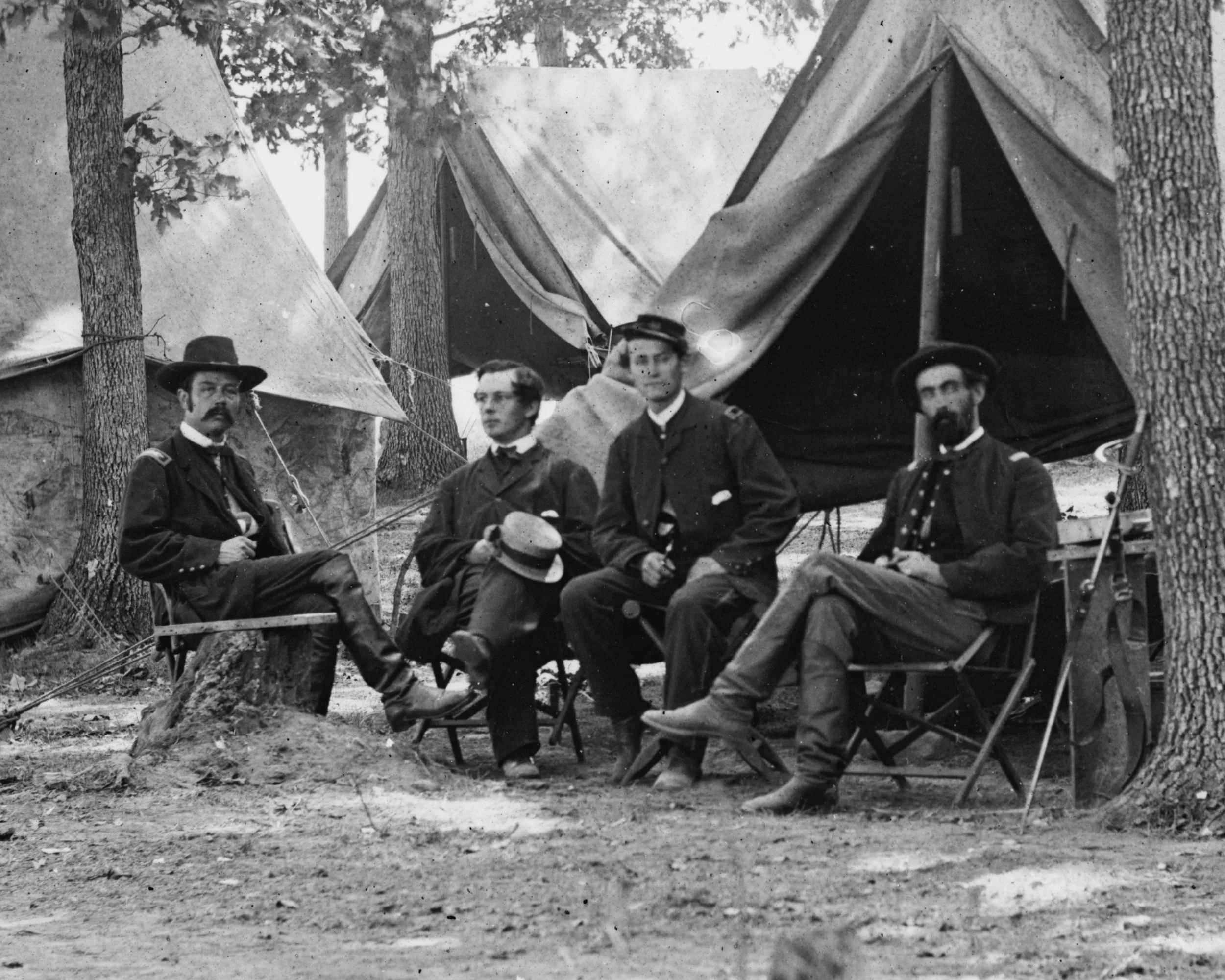

Cpt Milton Cline (seated center) with his scouts including his second in command Daniel Cole (seated right of Cline)

A group of BMI scouts, camp cooks, and clerks in camp at Brandy Station in 1864